PiP’s Clinical Guidelines

From the outset, PiP was seen as a means through which knowledge about best practice could be shared among clinicians. This included providing support to junior doctors and it was also a means of bringing isolated practitioners in more specialist areas of clinical practice into a more supportive environment. The Partnership offered the possibility of sharing the effort of securing and codifying that knowledge in the first place.

From the outset, PiP was seen as a means through which knowledge about best practice could be shared among clinicians. This included providing support to junior doctors and it was also a means of bringing isolated practitioners in more specialist areas of clinical practice into a more supportive environment. The Partnership offered the possibility of sharing the effort of securing and codifying that knowledge in the first place.

In December 1997, just a few months after the idea of of PiP was floated, the Labour Government’s first health White Paper – The New NHS – had given great emphasis to the specification of appropriate, effective, evidence-based care and the narrowing of variation in clinical practice. Clinical guidelines were a favoured tool, as a BMJ Series of articles noted. The Editorial is from 9 August 1997.

In December 1997, just a few months after the idea of of PiP was floated, the Labour Government’s first health White Paper – The New NHS – had given great emphasis to the specification of appropriate, effective, evidence-based care and the narrowing of variation in clinical practice. Clinical guidelines were a favoured tool, as a BMJ Series of articles noted. The Editorial is from 9 August 1997.

PiP’s guidelines project got going ‘for real’ towards through the summer of ’98, though the meetings of March and May rehearsed the rationale for the project and the resources needed to make it happen.

John Alexander, PiP’s Lead Clinician, was there at the start, and he took responsibility for convening the project group. Colleagues from Shrewsbury, Walsall, Crewe, Macclesfield and Burton brought a range of views to the group, but there was an obvious starting point; to compile existing guidelines from each of the hospitals into one place. In some, guidelines were already in .html format and online. The web could be the data collection tool and the guidelines would then be available to PiP members and password protected. The guidelines used by different hospitals might well differ, however, and so John talked about the need for a review mechanism, which would also take account of the care practices in tertiary centres. New, PiP guidelines, could follow.

But first, the platform. Steve Cropper suggested it might be a good, practical project for a Computer Science Masters student at Keele and at, the next meeting, a student and supervisor duly attended. John had contacted the NHS Information Authority which allocated space to PiP on its ‘nursery server’ and a web domain nww.pip.wmids.nhs.uk, and places on a two-day training course. The minutes of the meeting (21st July, 1999) record that:

“[The student]has designed a database-based website which was demonstrated in part during the meeting. Data entry into the website will be a long process and we may need to employ somebody for a short term to achieve this. Once the bulk of the documents have been included, maintenance and updating should not be too difficult. Demonstration of a fully working prototype will be carried out on 12.8.99 at 15.30 hours in John Alexander’s office.”

The minutes also note that “A discussion took place regarding parent participation in the group. It was suggested that this might be considered for individual guideline preparation.”

By August, the group had identified 209 guideline titles (my handwritten note records someone describing them as ‘mostly bog-standard guidelines’) and funding to enable conversion to .html format. Discussion turned to the commissioning of new guidelines for and by PiP members. Diabetic Ketoacidosis was the number 1 contender, but there was a broader question about the process to be used to commission and prepare guidelines and to maintain them. The answer came from the West Mercia Bedside Guidelines Group, led by a Consultant Physician at the North Staffs, Charles Pantin. This Group (like PiP, a subscription partnership) had the necessary resources and a method for producing what were termed ‘evidence-challenged guidelines’. These were guidelines that would work in any of the hospitals around PiP, rather than the ‘rarified’ environment of teaching hospitals where the research and evidence-gathering resources were substantially based, but which had specialist practices not always suited to, or usable by, paediatricians working in a District General Hospital. PiP’s guidelines followed the method of testing consensus descriptions of best local practice against available evidence.

The initial website was, essentially, a gathering ground and a tool for review and comparison of the existing guidelines. Although PiP’s guidelines were, then, for a while, loaded onto PiP’s website, and they are also, customarily, circulated to Trusts for upload to their intranets, they are most elegant, most accessible at the bedside, and most tactile, …. Well, in the pocket-size booklet. Member organizations receive a quota of the print run, and the guidelines are available to non-members for a modest sum. There are takers!

From Core Group minutes 19.9.2017

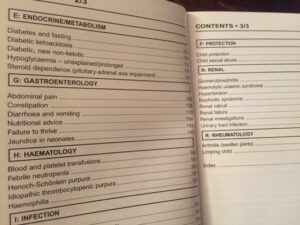

Issue 01 of the Guidelines was published in September 2004. It contained 60 entries in eleven sections, from Anaesthetics and Critical Care to (Child) Protection. Diabetic ketoacidosis was there, as were Kawasaki Disease and Long line insertion. The Preface explained the philosophy and practice.

Issue 01 of the Guidelines was published in September 2004. It contained 60 entries in eleven sections, from Anaesthetics and Critical Care to (Child) Protection. Diabetic ketoacidosis was there, as were Kawasaki Disease and Long line insertion. The Preface explained the philosophy and practice.

A cycle of two years was set for editions. Towards the end of 2022, and with only one cycle’s worth of slippage over the intervening years, Issue 09 was received from the printers and circulated to members: 105 guidelines in thirteen sections, and the Top Tips on top.

Top tips? The Sixth edition of the guidelines was special. It came out in 2015 and added not only new speciality areas, but also ‘Top Tips’ that the Shropshire Young Health Champions had developed to improve communication with children and young people.